Your basket is currently empty!

Tag: tracking

Employee monitoring software became the new normal during COVID-19. It seems workers are stuck with it

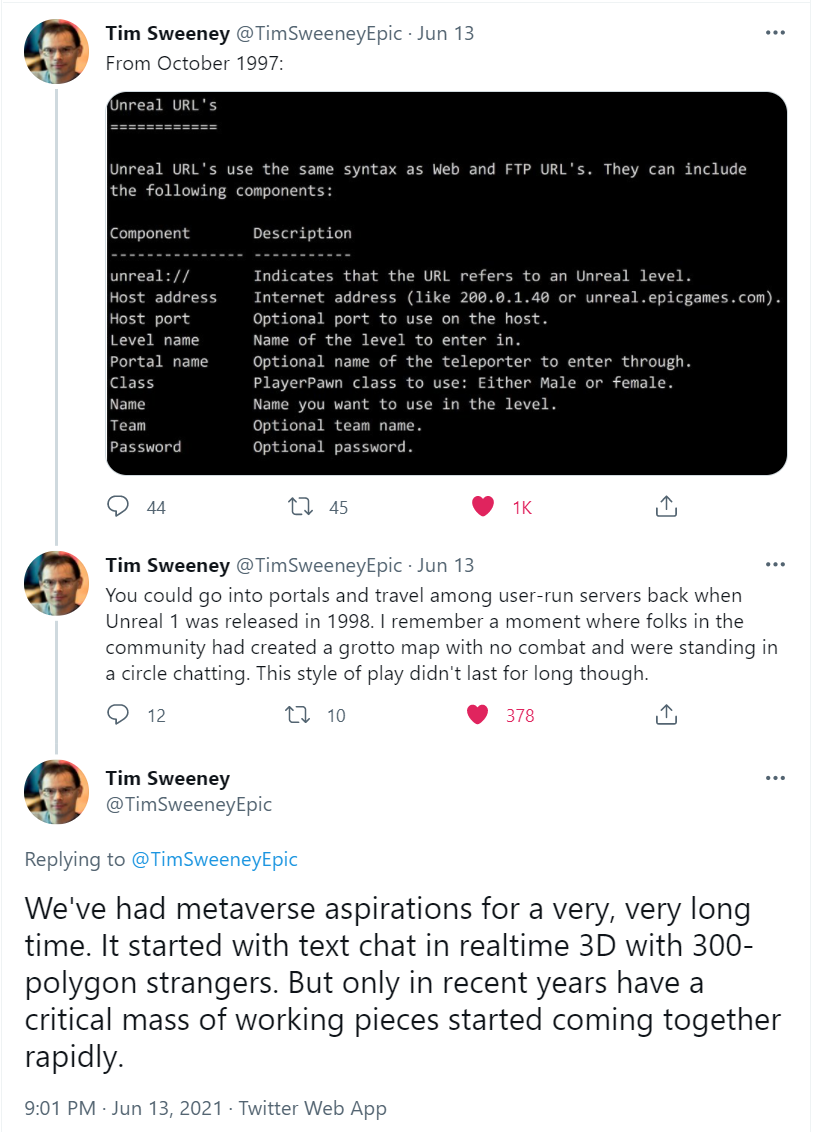

Many employers say they’ll keep the surveillance software switched on — even for office workers.In early 2020, as offices emptied and employees set up laptops on kitchen tables to work from home, the way managers kept tabs on white-collar workers underwent an abrupt change as well.

Bosses used to counting the number of empty desks, or gauging the volume of keyboard clatter, now had to rely on video calls and tiny green “active” icons in workplace chat programs.

In response, many employers splashed out on sophisticated kinds of spyware to claw back some oversight.

“Employee monitoring software” became the new normal, logging keystrokes and mouse movement, capturing screenshots, tracking location, and even activating webcams and microphones.

At the same time, workers were dreaming up creative new ways to evade the software’s all-seeing eye.

Now, as workers return to the office, demand for employee tracking “bossware” remains high, its makers say.

Surveys of employers in white-collar industries show that even returned office workers will be subject to these new tools.

What was introduced in the crisis of the pandemic, as a short-term remedy for lockdowns and working from home (WFH), has quietly become the “new normal” for many Australian workplaces.

A game of cat-and-mouse jiggler

For many workers, the surveillance software came out of nowhere.

The abrupt appearance of spyware in many workplaces can be seen in the sudden popularity of covert devices designed to evade this surveillance.

Before the pandemic, “mouse jigglers” were niche gadgets used by police and security agencies to keep seized computers from logging out and requiring a password to access.

An array of mouse jigglers for sale on eBay.(Supplied: eBay) Plugged into a laptop’s USB port, the jiggler randomly moves the mouse cursor, faking activity when there’s no-one there.

When the pandemic hit, sales boomed among WFH employees.

In the last two years, James Franklin, a young Melbourne software engineer, has mailed 5,000 jigglers to customers all over the country — mostly to employees of “large enterprises”, he says.

Often, he’s had to upgrade the devices to evade an employers’ latest methods of detecting and blocking them.

It’s been a game of cat-and-mouse jiggler.

“Unbelievable demand is the best way to describe it,” he said.

And mouse jigglers aren’t the only trick for evading the software.

In July last year, a Californian mum’s video about a WFH hack went viral on TikTok.

Leah told how her computer set her status to “away” whenever she stopped moving her cursor for more than a few seconds, so she had placed a small vibrating device under the mouse.

“It’s called a mouse mover … so you can go to the bathroom, free from paranoia.”

Others picked up the story and shared their tips, from free downloads of mouse-mimicking software to YouTube videos that are intended to play on a phone screen, with an optical mouse resting on top. The movement of the lines in the video makes the cursor move.

“A lot of people have reached out on TikTok,” Leah told the ABC.

“There were a lot of people going, ‘Oh, my gosh, I can’t believe I haven’t heard of this before, send me the link.’”

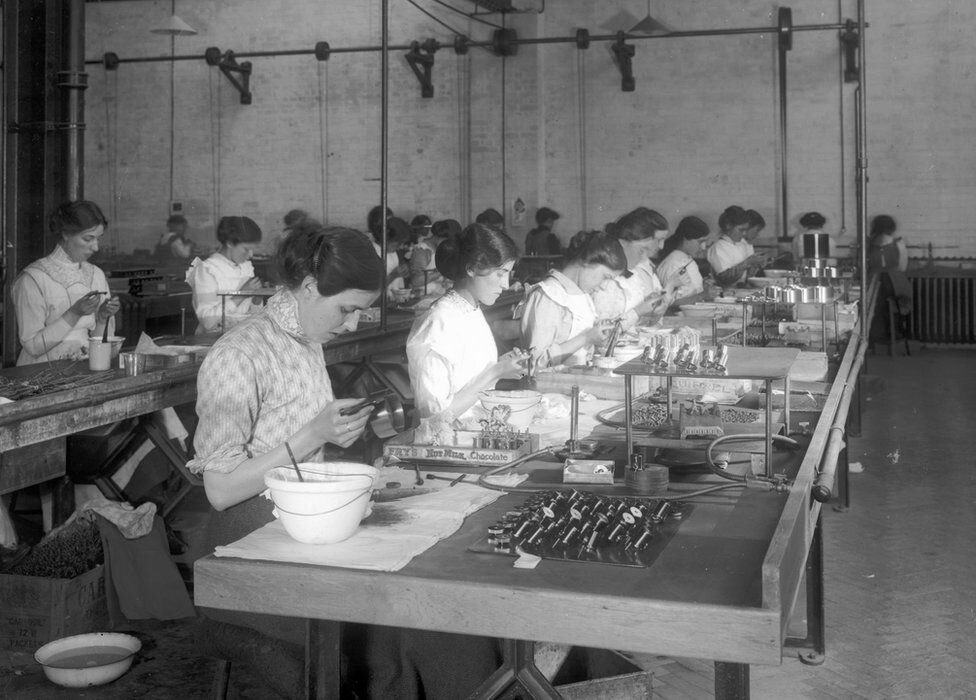

Tracking software sales are up — and staying up

On the other side of the world, in New York, EfficientLab makes and sells an employee surveillance software called Controlio that’s widely used in Australia.

It has “hundreds” of Australian clients, said sales manager Moath Galeb.

“At the beginning of the pandemic, there was already a lot of companies looking into monitoring software, but it wasn’t such an important feature,” he said.

“But the pandemic forced many people to work remotely and the companies started to look into employee monitoring software more seriously.”

Managers can track employees’ productivity scores on a realtime dashboard.(Supplied: Controlio) In Australia, as in other countries, the number of Controlio clients has increased “two or three times” with the pandemic.

This increase was to be expected — but what surprised even Mr Galeb was that demand has remained strong in recent months.

“They’re getting these insights into how people get their work done,” he said.

The most popular features for employers, he said, track employee “active time” to generate a “productivity score”.

Managers view these statistics through an online dashboard.

Advocates say this is a way of looking after employees, rather than spying on them.

Bosses can see who is “working too many hours”, Mr Galeb said.

“Depending on the data, or the insights that you receive, you get to build this picture of who is doing more and doing less.”

Nothing new for blue-collar workers

But those being monitored are likely to see things a little differently.

Ultimately, how the software is used depends on what power bosses have over their workers.

For the increasing number of people in insecure, casualised work, these tools appear less than benign.

In an August 2020 submission to a NSW senate committee investigating the impact of technological change on the future of work, the United Workers Union featured the story of a call centre worker who had been working remotely during the pandemic.

One day, the employer informed the man that monitoring software had detected his apparent absence for a 45-minute period two weeks earlier.

The submission reads:

Unable to remember exactly what he was doing that particular day, the matter was escalated to senior management who demanded to know exactly where he physically was during this time. This 45-minute break in surveillance caused considerable grief and anxiety for the company. A perceived productivity loss of $27 (the worker’s hourly rate) resulted in several meetings involving members of upper management, formal letters of correspondence, and a written warning delivered to the worker.

There were many stories like this one, said Lauren Kelly, who wrote the submission.

“The software is sold as a tool of productivity and efficiency, but really it’s about surveillance and control,” she said.

“I find it very unlikely it would result in management asking somebody to slow down and do less work.”

Ms Kelly, who is now a PhD candidate at RMIT with a focus on workplace technologies including surveillance, says tools for tracking an employee’s location and activity are nothing new — what has changed in the past two years is the types of workplaces where they are used.

Before the pandemic, it was more for blue-collar workers. Now, it’s for white-collar workers too.

“Once it’s in, it’s in. It doesn’t often get uninstalled,” she said.

“The tracking software becomes a ubiquitous part of the infrastructure of management.”

The ‘quid pro quo’ of WFH?

More than half of Australian small-to-medium-sized businesses used software to monitor the activity and productivity of employees working remotely, according to a Capterra survey in November 2020.

That’s about on par with the United States.

“There’s a tendency in Australia to view these workplace trends as really bad in other places like the United States and China,” Ms Kelly said.

“But actually, those trends are already here.”

The latest software claims to monitor employee emotions like happiness and sadness.(Supplied: StaffCircle) In fact, a 2021 survey suggested Australian employers had embraced location-tracking software more warmly than those of any other country.

Every two years, the international law firm Herbert Smith Freehills surveys thousands of its large corporate clients around the world for an ongoing series of reports on the future of work.

In 2021, it found 90 per cent of employers in Australia monitor the location of employees when they work remotely, significantly more than the global average of less than 80 per cent.

Many introduced these tools having found that during lockdown, some employees had relocated interstate or even overseas without asking permission or informing their manager, said Natalie Gaspar, an employment lawyer and partner at Herbert Smith Freehills.

“I had clients of mine saying that they didn’t realise that their employees were working in India or Pakistan,” she said.

“And that’s relevant because there [are] different laws that apply in those different jurisdictions about workers compensation laws, safety laws, all those sorts of things.”

She said that, anecdotally, many of her “large corporate” clients planned to keep the employee monitoring software tools — even for office workers.

“I think that’s here to stay in large parts.”

And she said employees, in general, accepted this elevated level of surveillance as “the cost of flexibility”.

“It’s the quid pro quo for working from home,” she said.

Is it legal?

The short answer is yes, but there are complications.

There’s no consistent set of laws operating across jurisdictions in Australia that regulate surveillance of the workplace.

In New South Wales and the ACT, an employer can only install monitoring software on a computer they supply for the purposes of work.

With some exceptions, they must also advise employees they’re installing the software and explain what is being monitored 14 days prior to the software being installed or activated.

In NSW, the ACT and Victoria, it’s an offence to install an optical or listening device in workplace toilets, bathroom or change rooms.

South Australia, Tasmania, Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland do not currently have specific workplace surveillance laws in place.

Smile, you’re at your laptop

Location tracking software may be the cost of WFH, but what about tools that check whether you’re smiling into the phone, or monitor the pace and tone of your voice for depression and fatigue?

These are some of the features being rolled out in the latest generation of monitoring software.

Zoom, for instance, recently introduced a tool that provides sales meeting hosts with a post-meeting transcription and “sentiment analysis”.

Zoom IQ for Sales offers a breakdown of how the meeting went.(Supplied: Zoom) Software already on the market trawls email and Slack messages to detect levels of emotion like happiness, anger, disgust, fear or sadness.

The Herbert Smith Freehills 2021 survey found 82 per cent of respondents planned to introduce digital tools to measure employee wellbeing.

A bit under half said they already had processes in place to detect and address wellbeing issues, and these were assisted by technology such as sentiment analysis software.

Often, these technologies are tested in call centres before they’re rolled out to other industries, Ms Kelly said.

“Affect monitoring is very controversial and the technology is flawed.

“Some researchers would argue it’s simply not possible for AI or any software to truly ‘know’ what a person is feeling.

“Regardless, there’s a market for it and some employers are buying into it.”

The movement of the second hand of an analogue wristwatch moves an optical mouse cursor a tiny amount.(Supplied: Reddit) Back in Melbourne, Mr Franklin remains hopeful that plucky inventors can thwart the spread of bossware.

When companies switched to logging keyboard inputs, someone invented a random keyboard input device.

When managers went a step further and monitored what was happening on employees’ screens, a tool appeared that cycled through a prepared list of webpages at regular intervals.

“The sky’s the limit when it comes to defeating these systems,” he said.

And sometimes the best solutions are low tech.

Recently, an employer found a way to block a worker’s mouse jiggler, so he simply taped his mouse to the office fan.

“And it dragged the mouse back and forth.

“Then he went out to lunch.”

Whoop’s New Wearable Can Go on Your Wrist—or in Your Clothes

Your workout apparel just got a lot smarter.

Slide Whoop’s new 4.0 fitness tracker into your shorts, leggings, shirt, or sports bra.PHOTOGRAPH: WHOOP ASK PEOPLE IF they’ve heard of the Whoop activity-tracking wearable and they’ll either look at you blankly or say they couldn’t work out, sleep, or live without it. It’s a wrist wearable aimed at fitness fanatics—pro and college athletes, CrossFitters and weekend warriors—and it stands out for a couple of reasons. For one, the only way to get a Whoop wearable is to pay a monthly or annual subscription fee. And two, one of its marquee features is that it tells wearers how much physical strain they can handle on any given day.

You might not think that business model would be worth $3.6 billion. But some investors—and an undisclosed number of subscribers—seem to think Whoop is a big whoop. Now, the Boston company is expanding its product line and getting into “smart” clothing: The Whoop module that’s normally worn on the wrist has been redesigned so that it can also be attached to Whoop-branded athletic apparel. The new Whoop, which the company has dubbed Whoop 4.0, is also the first consumer product on the market to ship with a new kind of super-charged silicon lithium battery.

“Smart clothes” have struggled to gain traction before, and when it comes to wearables specific to the wrist, Apple dominates that market. But Whoop thinks its combination of continuous health monitoring and new “Any-Wear” technology, which is supposed to determine where on the body you’re wearing your Whoop and adjust your data-tracking accordingly, will set it apart in a sea of tracking tech.

“We’ve long felt that wearable technology should be cool or invisible. Those are the only two paradigms we want to develop on,” says Will Ahmed, Whoop’s cofounder and chief executive. “In terms of ‘cool,’ it’s an area we’ve focused on a lot historically, making it something that you can dress up or dress down. But ‘invisible’ is, ‘How do we make it disappear?’”

Buyers might also notice their dollars disappearing when they factor in a $24 per month subscription to Whoop’s fitness-tracking software platform—the hardware is included in that—and the cost of Whoop’s new apparel, which includes $69 boxers, a $79 sports bra, and $109 leggings. But serious exercisers who are used to paying top price for fitness apparel might not bat an eye at those costs. (And if they did bat an eye, Whoop would certainly track it.)Track Star

The new Whoop fitness tracker can be worn in a band on your wrist like before, or it can slide into one of the company’s new workout apparel pieces, like these leggings. PHOTOGRAPH: WHOOP Whoop tracks heart rate variability, resting heart rate, respiratory rate, and sleep. The new Whoop 4.0 sensor module still tracks all of the above, but it’s 33 percent smaller than the third-generation Whoop, says Ahmed. This is partly what makes the Whoop clothing line possible: The device had to be small enough to fit comfortably in apparel pockets. It also has to sit snug to the skin, so that there’s a “good agreement between the sensor and your skin” and accurate data can be captured, says John Capodilupo, another cofounder and the company’s chief technology officer.

Because Whoop thinks that customers will attach the Whoop module to different parts of their body on any given day—which is one way to convince the Apple Watch-wearing crowd that they could also buy into Whoop—it developed an algorithm that automatically detects where the Whoop is being placed and processes biometric data accordingly. The software was developed based on more than 20,000 data sets gathered from thousands of beta testers wearing both Whoop tech and standard heart-rate-monitoring chest straps, Capodilupo says. The company has not published its methodology or the full results of this research.

The Whoop 4.0, which goes on sale this week and ships later in September, has some more new features. It vibrates during sleep cycles to wake up wearers. It has a built-in pulse oximeter as well as a skin temperature sensor. Those are not uncommon in activity-tracking wearables, though.

Still works on the wrist if that’s where you like it. PHOTOGRAPH: WHOOP What’s especially interesting about the new Whoop is its lithium-ion battery technology. It’s the first consumer product to ship with battery tech developed by Sila Nanotechnologies, a buzzy Alameda, California, company that uses microscopic silicon particles to “supercharge lithium-ion cells when they’re used as the battery’s negative electrode,” as WIRED reported last year.

Sila Nano doesn’t actually make the batteries. It provides its proprietary silicon nanoparticles and recipes to battery makers. The company’s founder, Gene Berdichevsky, thinks this battery tech will eventually make its way into electric vehicles. (Berdichevsky was also an early employee at Tesla.) But he says it’s challenging to scale the manufacturing equipment for Sila Nano’s materials to the size and volume needed for electric vehicles, so it’s starting out with small electronics.

What this means for Whoop wearers is that version 4.0 has the same expected battery life as previous Whoop bands—around five days of continuous tracking per charge—but the physical battery is smaller. And as with any battery technology that pushes the limits of chemistry and physics, years of research and development were required before the tech could be considered commercially viable; silicon has a tendency to swell, which stresses batteries. But Berdichevsky has said in the past he believes Sila Nano has solved this “expansion” problem with its nanoparticles.Wear It Out

Whoop sells a 4.0-compatible sports bra as well. PHOTOGRAPH: WHOOP It remains to be seen whether people want to wear “smart clothes,” or if wrist wearables are providing enough value for wearers for now. Over the past decade, tech behemoths like Intel, as well as lesser-known upstarts like Athos, OmSignal, and Sensoria, have dabbled in sensor-filled clothing, the idea being that it provides a more passive tracking experience while the wearer is being active. The results have been mixed.Most Popular

Stefan Olander, a former Nike executive who launched the FuelBand wrist wearable for Nike back in 2012, said in an email that connected apparel involves “much more friction than wrist-worn devices. Anything that requires batteries, charging, pairing, is harder to wash, or anything else that requires a change in behavior, is going to have a hard time becoming a truly scalable consumer proposition.” (Olander, who has been working on another not-yet-released connected fitness product, was not briefed specifically on Whoop’s new product, and was speaking broadly about the product category.)

“True scale comes from simple solutions that enhance people’s lives, with as little unnecessary change as possible,” Olander says.

Whoop, of course, thinks it is that simple solution, with its screenless, customizable bands, wear-it-and-forget-about-it battery life, and now, its ability to slip right into your workout clothes. It just also happens to target a very specific demographic that will pay to subscribe to a workout wearable—and now, will also pay top dollar for its apparel.

FROM WIRED