A first-of-its-kind security analysis of iOS Find My function has demonstrated a novel attack surface that makes it possible to tamper with the firmware and load malware onto a Bluetooth chip that's executed while an iPhone is "off."

The mechanism takes advantage of the fact that wireless chips related to Bluetooth, Near-field communication (NFC), and ultra-wideband (UWB) continue to operate while iOS is shut down when entering a "power reserve" Low Power Mode (LPM).

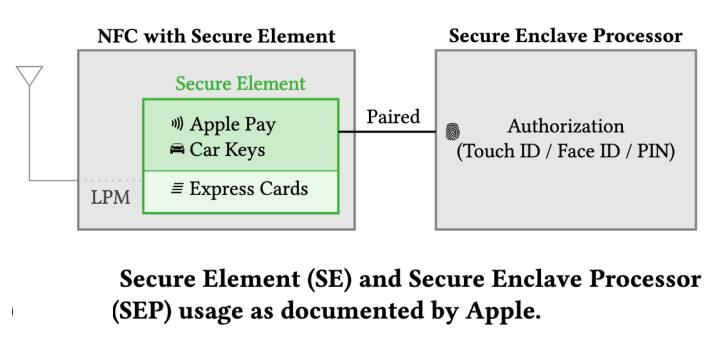

While this is done so as to enable features like Find My and facilitate Express Card transactions, all the three wireless chips have direct access to the secure element, academics from the Secure Mobile Networking Lab (SEEMOO) at the Technical University of Darmstadt said in a paper.

"The Bluetooth and UWB chips are hardwired to the Secure Element (SE) in the NFC chip, storing secrets that should be available in LPM," the researchers said.

"Since LPM support is implemented in hardware, it cannot be removed by changing software components. As a result, on modern iPhones, wireless chips can no longer be trusted to be turned off after shutdown. This poses a new threat model."

The findings are set to be presented at the ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks (WiSec 2022) this week.

The LPM features, newly introduced last year with iOS 15, make it possible to track lost devices using the Find My network. Current devices with Ultra-wideband support include iPhone 11, iPhone 12, and iPhone 13.

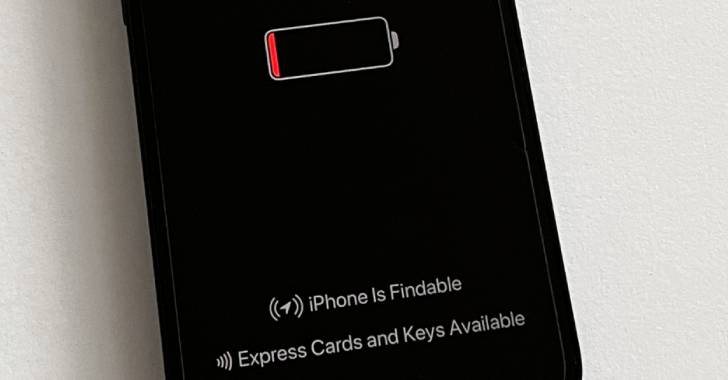

A message displayed when turning off iPhones reads thus: "iPhone remains findable after power off. Find My helps you locate this iPhone when it is lost or stolen, even when it is in power reserve mode or when powered off."

Calling the current LPM implementation "opaque," the researchers not only sometimes observed failures when initializing Find My advertisements during power off, effectively contradicting the aforementioned message, they also found that the Bluetooth firmware is neither signed nor encrypted.

By taking advantage of this loophole, an adversary with privileged access can create malware that's capable of being executed on an iPhone Bluetooth chip even when it's powered off.

However, for such a firmware compromise to happen, the attacker must be able to communicate to the firmware via the operating system, modify the firmware image, or gain code execution on an LPM-enabled chip over-the-air by exploiting flaws such as BrakTooth.

Put differently, the idea is to alter the LPM application thread to embed malware, such as those that could alert the malicious actor of a victim's Find My Bluetooth broadcasts, enabling the threat actor to keep remote tabs on the target.

"Instead of changing existing functionality, they could also add completely new features," SEEMOO researchers pointed out, adding they responsibly disclosed all the issues to Apple, but that the tech giant "had no feedback."

With LPM-related features taking a more stealthier approach to carrying out its intended use cases, SEEMOO called on Apple to include a hardware-based switch to disconnect the battery so as to alleviate any surveillance concerns that could arise out of firmware-level attacks.

"Since LPM support is based on the iPhone's hardware, it cannot be removed with system updates," the researchers said. "Thus, it has a long-lasting effect on the overall iOS security model."

"Design of LPM features seems to be mostly driven by functionality, without considering threats outside of the intended applications. Find My after power off turns shutdown iPhones into tracking devices by design, and the implementation within the Bluetooth firmware is not secured against manipulation."

Source